I want to begin by saying I have never been a fan of ‘New Year Resolutions.’ I have always thought that if you would like to start something – whether it is to exercise or eat healthy – why not start that moment, why wait till the new year?

As I reflect on the ending of this year, 2020, it was not until recently that I begin to ponder the idea of making resolutions for myself for the new year. It makes me a slight hypocrite, but I wonder if making resolutions help increase the likelihood of accomplishing them.

In most cases, individuals will begin firm in their resolutions and tasks but then start to go in a downwards spiral later in the year, only completely to fail by mid-March, but why is that?

I took it upon myself to do some research on ‘New Year Resolutions’ and if they work, and what are some ways that could increase the likelihood of them being successfully completed.

- Lose weight

- Stop smoking

- Start budgeting

- Become more organised

- Eat better

- Exercise more

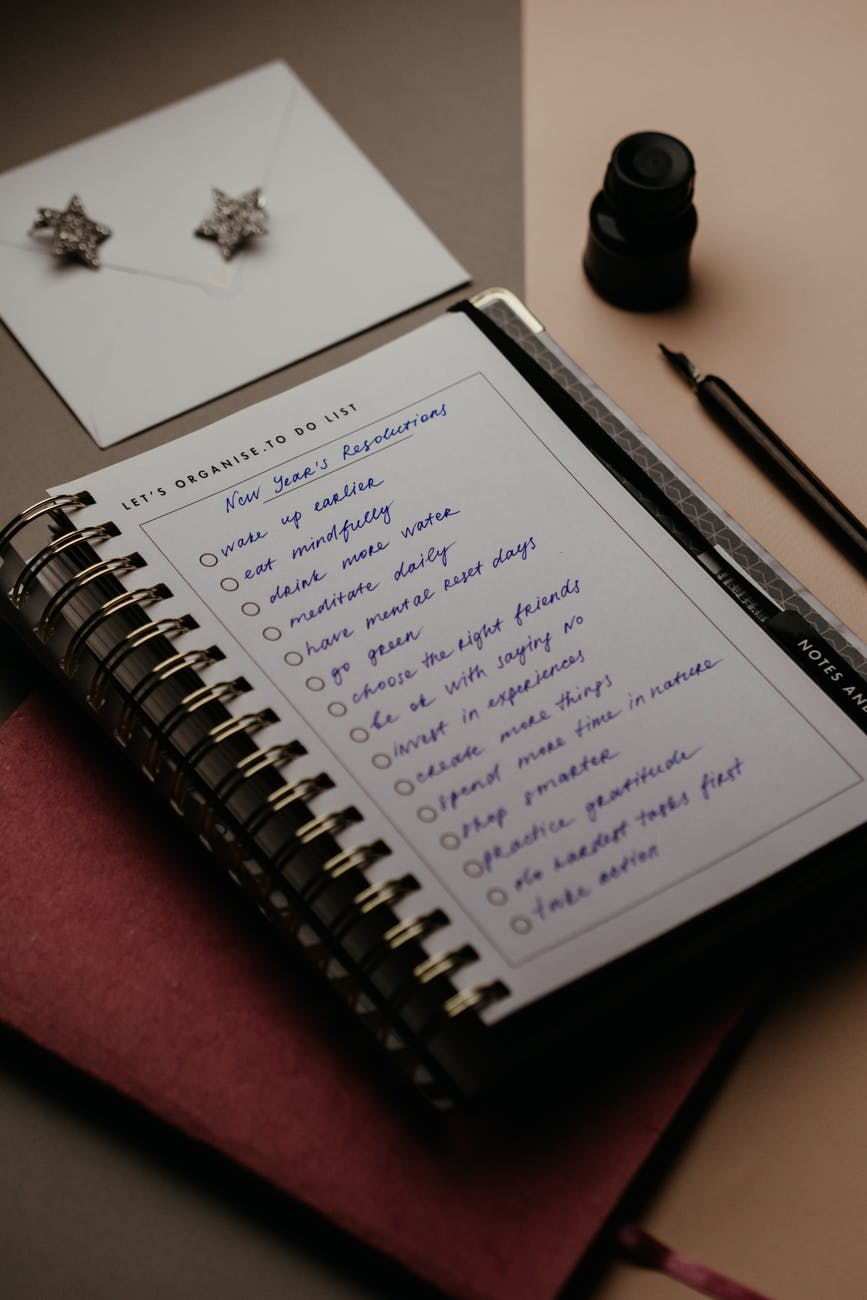

In a Veterinary Nursing Journal, Brown (2006) writes about some of the most common new year resolutions are (please refer to the list on the left).

In a paper written by Dr. Chiarello (2020) states, although our intentions of successfully completing our personal resolutions, they last only briedly and are then to be “thrown by the wayside”, perhaps due to them being simplly out of reach (Chiarello, 2020).

Our resolutions may be too much to handle by ourselves but only may benefit by having others around us, giving support, and keeping us on track. It may be that self-initiated attempts to change one’s behavior require more self-control than we can muster. A report written by Marlatt and Kaplan (1972) surveyed self-monitoring participants in completing self-initiated attempts in behavioural change from new year resolutions. They found a general “success rate” of 75% of resolutions was kept over a three month time period, excluding resolutions involving weight loss, while 25% of resolutions were reported to be broken during or towards the end of the three month period (Marlatt & Kaplan, 1972). It appeared that the most difficult resolutions to keep were physical health (64% broken), smoking (60% broken) and, personal behaviour (31% broken) (Marlatt & Kaplan, 1972).

Another paper discussed similar findings on success and failure rates of primary resolutions after six-months. This paper was written on the changes in processes and reported outcomes of resolution by Norcross, Ratzin, and Payne (1989) and found that 40% of participants kept their resolution after six months. The reported success rates may have exaggerated due to the volunteered self-report and the study’s demand characteristics.

Self-monitoring has also been explained in terms of “feedback look” operation or “knowledge of results function (Norcross, Ratzin, & Payne, 1989). This operation provides self-monitoring as a necessary comparison measure during the acquisition of new behaviours and has been found effective during self-initiated changes for target behaviours (Norcross, Ratzin, & Payne, 1989).

Although most of us who make new year resolutions may fall off track by March, some methods may help us complete them. When making new years resolutions, or even if you have already made some, do not give yourself a list of resolutions to be made over a lifetime – make a small list of specific and realistic goals you can achieve by the new year (Brown, 2006). Write out your resolutions on a paper and place them in sight in a common area. This paper will be used as a reminder for yourself and maintain your self-monitoring attempts to complete your task(s). Lastly, as said earlier, invite a friend or partner to help achieve your resolution – it could be someone who shares the same/similar resolutions. You could help keep each other on track in completing them.

Personally, my new years resolutions are to be better to myself – improving my physical and mental health – especially during this pandemic. Hopefully, by attempting to be successful in this resolution, I will not end up like the suggested 60% of people who break their resolutions, but who knows, I’ve never been a fan of new years resolutions.

References:

Brown, J.. (2006). New year’s resolutions. Veterinary Nursing Journal, 21(1), 28–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/17415349.2006.11013439

Chiarello, Cynthia M. PT, PhD; Editor-in-Chief New Year, New Resolutions, Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy: January/March 2020 – Volume 44 – Issue 1 – p 1-2 doi: 10.1097/JWH.0000000000000160

Marlatt, G. A., & Kaplan, B. E.. (1972). Self-Initiated Attempts to Change Behavior: A Study of New Year’s Resolutions. Psychological Reports, 30(1), 123–131. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1972.30.1.123

Norcross, J. C., Ratzin, A. C., & Payne, D.. (1989). Ringing in the new year: The changeprocesses and reported outcomes of resolutions. Addictive Behaviors, 14(2), 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(89)90050-6